By now we're used to the fact that anything can happen in the Metamorphoses. This "fact" shouldn't inure us to the singularly strange transitions and juxtapositions woven into the text, because we are probably meant to be perplexed by them. The rapid reader will find sheer arbitrariness in a segue that moves swiftly from the end of a 400+ line speech by an ancient Greek philosopher to a telegraphic note on the death of Numa, to the transformation of his consort Egeria, to the sudden intrusion of the voice of a figure who claims to be the dead Hippolytus, now restored and assisting Diana in Aricia under the new identity of Virbius. And that fast reader's reaction would be understandable. But perhaps there's more to it.

For purposes of making some headway here, note that Ovid has turned from the voice of Pythagoras to the texts of several of Euripides' tragedies -- the Orestes, Iphigeneia at Tauris and Hippolytus. These plays deal with the fates of two of the great Greek houses (oikoi) -- of Atreus and of Theseus. (Of course the Oresteia of Aeschylus is involved as well.)

These two tales couldn't be more different, and their differences are worth pondering. For example, Agamemnon's son Orestes (who was sent to live in Phocis after his mother, Clytemnestra, begins her involvement with Aegisthus) is ordered by the gods to kill his mother. Pursued by the Erinyes, he goes insane before being restored, judged not guilty, cleansed (by nine men at Troezen), and elevated to succeed his father as ruler of Mycenae. He also recovers Hermione, daughter of Helen and Paris, who was betrothed to him by Tyndareus, but who, after he went insane, was given by Menelaos to Neoptolemus.

In a nutshell, the concern with Orestes is with intra-familial murder, revenge, justice, and the recovering of kingly succession. The kingdom passes from Agamemnon to his son, but not in quite the ceremonial and orderly fashion most states would prefer.

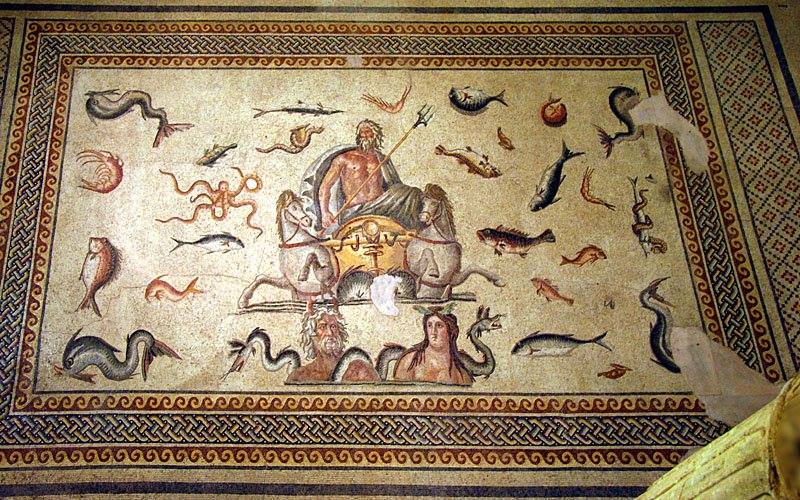

The house of Theseus is not so much of a house. Through his human father Aegeus (who shares paternity with Poseidon), Theseus can trace his line to Erichthonius, the allegedly autochthonous early king of Athens. Theseus had a somewhat peculiar marriage with the Amazon Hippolyta (the only Amazon ever to wed any man), and Hippolytus was their child. After the death of Hippolyta, Hippolytus was sent to live in Troezen with his great-grandfather, Pittheus, while Theseus married Minos's daughter Phaedra, Ariadne's sister. Phaedra's unquenchable desire for Hippolytus leads to his brutal death. She lies to Theseus, claiming Hippolytus had assaulted her, and Theseus uses one of three wishes granted him by Poseidon to cause the death of his son.

The figure of a bull appears in a giant wave, frightening Hippolytus's horses, and fulfilling the apparent meaning of his name, which can mean "unleasher of horses," or, "destroyed by horses."

So, two stories of royal houses, fathers and sons, things going awry. In one, a son kills his natural mother; in the other, a stepmother brings about the death of the king's son. In one, order is restored, in the other, the house ends, but the son has a curious afterlife.

What brings these tales together in the Arician grove of "Oresteian Diana"? Why, after listening for quite some time to the voice of Pythagoras, do we suddenly out of the blue hear Hippolytus speaking to Egeria? What is at stake in this strange juxtaposition, and in the admittedly in-credible tale of how this tragic figure became Virbius? (Virgil's version of that tale is told in Aeneid 7).

To get a sense of the background, it might be useful to look at two of Ovid's Heroides in connection with this part of Metamorphoses 15: The letter of Hermione to Orestes, and the letter of Phaedra to Hippolytus.

|

| Orestes and Pylades kill Aegisthus |

In a nutshell, the concern with Orestes is with intra-familial murder, revenge, justice, and the recovering of kingly succession. The kingdom passes from Agamemnon to his son, but not in quite the ceremonial and orderly fashion most states would prefer.

|

| Athena, Orestes, Priestesses at Delphi |

The house of Theseus is not so much of a house. Through his human father Aegeus (who shares paternity with Poseidon), Theseus can trace his line to Erichthonius, the allegedly autochthonous early king of Athens. Theseus had a somewhat peculiar marriage with the Amazon Hippolyta (the only Amazon ever to wed any man), and Hippolytus was their child. After the death of Hippolyta, Hippolytus was sent to live in Troezen with his great-grandfather, Pittheus, while Theseus married Minos's daughter Phaedra, Ariadne's sister. Phaedra's unquenchable desire for Hippolytus leads to his brutal death. She lies to Theseus, claiming Hippolytus had assaulted her, and Theseus uses one of three wishes granted him by Poseidon to cause the death of his son.

The figure of a bull appears in a giant wave, frightening Hippolytus's horses, and fulfilling the apparent meaning of his name, which can mean "unleasher of horses," or, "destroyed by horses."

So, two stories of royal houses, fathers and sons, things going awry. In one, a son kills his natural mother; in the other, a stepmother brings about the death of the king's son. In one, order is restored, in the other, the house ends, but the son has a curious afterlife.

What brings these tales together in the Arician grove of "Oresteian Diana"? Why, after listening for quite some time to the voice of Pythagoras, do we suddenly out of the blue hear Hippolytus speaking to Egeria? What is at stake in this strange juxtaposition, and in the admittedly in-credible tale of how this tragic figure became Virbius? (Virgil's version of that tale is told in Aeneid 7).

To get a sense of the background, it might be useful to look at two of Ovid's Heroides in connection with this part of Metamorphoses 15: The letter of Hermione to Orestes, and the letter of Phaedra to Hippolytus.

No comments:

Post a Comment