Even then, the horses’ madness would not have exhausted my strength, if a wheel had not broken, and been wrenched off, as the axle hub, round which it revolves, struck a tree. Meta. 15.

The story Hippolytus tells of his own death has to be one of the more semantically charged moments in the Metamorphoses. It would go far beyond the bounds of a blog post to develop a full reading of his character and acts in book 15 and in the poem as a whole. Suffice it to say Hippolytus speaks, as we've noted, without preparation or introduction, and immediately strikes an odd note.

He's not very sympathetic to mourning Egeria, and goes on to recount his chariot crash scene, as if it somehow trumps the nymph's tale of loss. Coming as it does after the long song of Pythagoras, the physicality of the description of his crash, the uncanny appearance of the mountainous wave and the bull, all this narrative energy inserts a strange shock between the reflections and prescriptions of the philosopher and the serene journey of serpentine Aesculapius that follows.

The disfiguring death of Hippolytus is enigmatic at all points: he's one of the greatest horsemen in the world, yet he dies neither in a war nor in an Olympic race, but in an accident involving no other "drivers." He is the son of Theseus, one of the most just, beloved, and balanced heroes of Greece, but he dies cursed by his father for an alleged crime of Venus, though he's a follower of Artemis. He is of the line of Pelops, who was the lover of Poseidon. The god is also his grandfather, yet it's Poseidon's gift that visits Theseus's curse upon Hippolytus.

To unravel this knot, we need to follow threads leading back to violent kings, acts of treachery, and an abandoned princess.

Hippolytus was the son and heir of Theseus and the Amazon Hippolyta (or Antiope). This could be no ordinary union -- as Elizabeth Vandiver notes, the Amazons were not chaste huntress-devotees of Diana. They were, in fact, warrior women who enslaved men, used them to reproduce, and often sold their male children as slaves, or killed them.

If nothing else, this union between Theseus and the Amazon suggests an almost limitless openness to possibility, to the other, in Theseus. This was a fellow who excelled at two things: 1) taking down sociopathic monsters, and 2) persuading independent parties -- whether Amazons, or towns and city-states of Greece -- to form lasting unions.

Less than fortunate marriages

Theseus can be thought of as a slightly more domesticated Heracles. The two share many attributes, but Theseus does not evince the uncontrolled rage that resulted, for example, in the death of Heracles' wife and children. He advanced the ordering of civility at the head of the most brilliant and influential polis in mainland Greece:

Theseus was the Athenian founding hero, considered by them as their own great reformer: his name comes from the same root as θεσμός ("thesmos"), Greek for "institution". He was responsible for the synoikismos ("dwelling together")—the political unification of Attica under Athens . . .Given this context, to note that Hippolytus shunned Aphrodite and followed Artemis is no longer just a personal statement about the young man -- it has political implications that challenge the roots of Theseus's unifying thrust -- the vision of a happy marriage of cities in a larger harmonious whole, through the proper ordering of self and other, desire and persuasion.

Pausanias reports that after the synoikismos, Theseus established a cult of Aphrodite Pandemos ("Aphrodite of all the People") and Peitho on the southern slope of the Acropolis.

Only one who powerfully believed in the powers of Peitho (Persuasion, Seduction) could imagine a happy household (synoikismos < syn + oikos: "dwelling together in the same house") consisting of a Greek hero and an Amazon. Or, for that matter, a successful union of the slayer of the Minotaur and the daughter of Minos (hence the Minotaur's half-sister) whose full sister Ariadne had been abandoned by the aforementioned hero after saving his bacon. Theseus never ran from a fight, but here was exceptional inherent risk.

Athenian expectations of promise linked to the son of Theseus are understandable. Like his father, Hippolytus was related through Aegeus (the mortal father of Theseus) to the royal line of Athens, while through his great-grandfather Pittheus he had the blood of Pelops. The dual-fathered birth of Theseus brought into a single bloodline the most powerful polis of Attica and the realm of "Pelops' Island" -- the Pelopponese. The stars were lining up to bring these two giant halves of Greece under one "roof."

The prospect beckoned that the two halves of Greece, linked by the narrow (6.3 km) Isthmus of Corinth, could be joined, and Theseus and his son were the kings to do it. Those hopes were forever dashed on the day Hippolytus's horses were gripped by terror.

Exiled from his father's house after the charges of Phaedra, Hippolytus was on his way from Athens to Pittheus's city of Troezen. As it happened, he was just crossing the slender neck of the Isthmus of Corinth when the sea rose up:

a horned bull emerged out of the bursting waters, standing up to his chest in the gentle breeze, expelling quantities of seawater from his nostrils and gaping mouth.... my fiery horses turned their necks towards the sea, and trembled, with ears pricked, disturbed by fear of the monster, and dragged the chariot, headlong, down the steep cliff.This was said to be the same place where Pelops competed against Oenomaus for the hand of the king's daughter, Hippodameia. She loved Pelops, but Oenomaus had already nailed the heads of a dozen of her suitors to the walls of his house in Pisa. Poseidon had given Pelops winged horses and a golden chariot, but after seeing the king's horses (a gift from his father Ares), Pelops developed a plan B. He bribed Oenomaus's charioteer Myrtilos to throw the race. In return, he promised Myrtilos a night with Hippodameia (whom the charioteer secretly loved) before he would consummate his marriage.

|

| Pelops and Hippodameia |

Myrtilos replaced the axles of Oenomaus's chariot with false axles made of beeswax that melted in the heat of the race, at the very moment Oenomaus was about to spear Pelops as he'd speared all the others. His chariot came apart, and Pelops killed him. The event had several fateful consequences:

- Pelops won the hand of Hippodameia ("horse tamer");

- Pelops became king of Pisa and eventually lord of the Pelopponese;

- Pelops founded the Olympian games in honor of his victory over Oenomaus;

- Myrtilos was thrown into the sea by Pelops as his winged chariot flew over the waves;

- Oenomaus died cursing Myrtilos, who died cursing Pelops;

- Pelops went on to father Atreus, Thyestes and Pittheus, among others;

- The house of Atreus -- Agamemnon, Menelaos and Orestes -- suffered the curse of Myrtilos, who was a son of Hermes.

The Horse Frightener

|

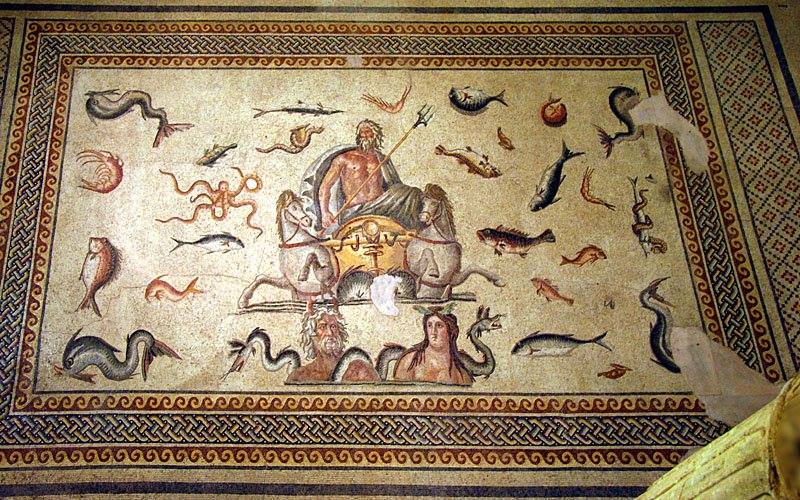

| Hippolytus, Bull |

Phaedra, the daughter of Minos, caused the rift between father and son, and the Cretan legend helps explain why the taraxippus -- the "horse-frightener" that killed Hippolytus -- was a bull. Long ago, before Minos had come to the throne, he felt his right to power was legitimate because of a gift from Poseidon:

Minos justified his accession as king and prayed to Poseidon for a sign. Poseidon sent a giant white bull out of the sea.[27] Minos was committed to sacrificing the bull to Poseidon,[28] but then decided to substitute a different bull. In rage, Poseidon cursed Pasiphaë, Minos' wife, with zoophilia.Minos' gift from the god of the sea bears an uncanny resemblance to Poseidon's brother Zeus at the moment he seduced Minos's mother Europa and bore her to Crete:

So the father and ruler of the gods, who is armed with the three-forked lightning in his right hand, whose nod shakes the world, setting aside his royal sceptre, took on the shape of a bull, lowed among the other cattle, and, beautiful to look at, wandered in the tender grass.

In color he was white as the snow that rough feet have not trampled and the rain-filled south wind has not melted.... Agenor’s daughter marveled at how beautiful he was and how unthreatening.As the white bull returned to seduce Pasiphaë and plague Minos, the hatred of Minoan Crete for Athens -- and for Theseus in particular -- can be said to come back in the form of a bull that steals his child, as Theseus had slain the Minotaur and stolen Ariadne, as Zeus had stolen Europa. With grim Euripidean irony, Theseus's son's death results from his father's' wish that's fulfilled by his father, Poseidon. The same figure that gave Minos accession to power destroys the line of succession for the house of Theseus.

Ovid has again taken a Greek tale to talk about how Rome is different from Greece. In Hippolytus's broken body, the hopeful political future of Greece was broken. As the pieces of the tale fall into place, Ovid's introduction of this character, and of this moment in his and Theseus's careers, offers an oblique view of the hope and tragedy bound up with kingship, political order, and the problem of succession in Greece, and now in Rome.

The question facing this and any reading of Ovid's Hippolytus arises from his return to life, and its implications for Ovid's sense of the prospects of Rome.

|

| Isthmus of Corinth |

No comments:

Post a Comment