“The universe is made of stories, not of atoms.” — Muriel Rukeyser

In the Metamorphoses of Ovid, Rukeyser's apothegm is apt -- at least until one remembers that the audience for his stories is often in the position of Athena in Book 5. She has arrived on Helicon to see the marvel of Hippocrene, the spring that upwelled from Pegasus's ungula striking the mountain's rock. Ungula can mean hoof, claw, or talon - a suitably ambiguous term for the extremities of a winged horse.

The Muses welcome Athena and suggest that if she did not have a larger part to play, she'd have been welcome in their "chorus." Art, Ovid is suggesting, is an ally of Wisdom. The Muses then go on to describe their terror at the assault of Pyraneus, followed by Calliope's tale of the goddesses' contest with the Pierides.

Athena here is in the position of hearing, after the fact, a story about a contest of stories (or songs), told by the winners of that contest. And if we think about it, we don't often hear stories told by losers, especially in the case of war. The dead tell few tales.

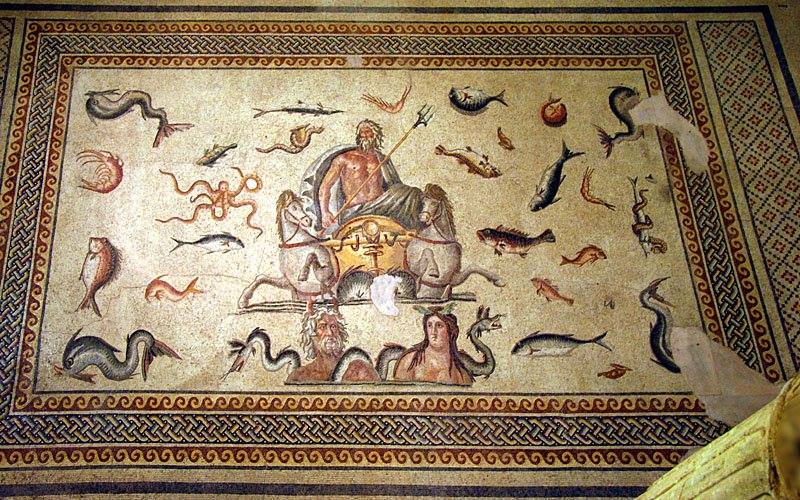

So just as Perseus gave us his version of how he killed Medusa, or Acoetes his tale of the appearance of Bacchus on his ship, the Muses tell of their victory over the nine daughters of Pierus. Big surprise, the competing story told by the Pierides is an alternate version of theogonic events -- a tale in which Typhoeus, the last monster born of Earth, frightens the Olympians, who rush to Egypt to hide themselves inside goats, rams, crows, cats, cows, ibis and fish. In other words, the Pierides tell a myth of the origin of how certain Olympians became associated in Egypt with certain creatures, but in "explaining" that origin, they are also alleging that the Olympian gods are (1) weaker than Earth-born Typhoeus, (2) scaredy cats, (3) associated with certain natural beings not because those beings manifest something of their nature or power, but because as gods of the sky without real power, they wish to hide from the Earth's hundred-headed giant, and (4), as William S. Anderson notes in his commentary on Ovid's Metamorphoses Books 1-5 (Bks 1-5) ,

,

the biased "art" of the Pierid involves slighting the metamorphosis by special verbs and reduction of the gods to epithets. First, then, Apollo is literally inside a raven and Bacchus inside a goat.

This should tell us something about Ovid's view of art and poetry. For him, metamorphosis underlies poetic and artistic creation. The Muses will go on to tell of several metamorphoses, but here their rivals are telling another kind of tale, in which greater force is all that matters, and what fools worship as gods are in fact shameful weaklings hiding inside creatures. This is not poetic -- no transformation is happening, no metaphor, just a deconstruction of cow-eyed Juno into Juno cowering inside a cow. A literal, denotative world devoid of wonder results from a loss, not of gods, but of confidence in the courage and power of gods. Literal language is the language of ninny gods.

The dramatization of the contest of the Muses vs. the Pierides then is Ovid's way of distinguishing false from true art, real inspiration from fake afflatus. This is what it means for art to be linked with Athena. Without her, you get tales told by idiots:

the one who had first declared the contest sang, of the war with the gods, granting false honours to the giants, and diminishing the actions of the mighty deities.

According to his Muses, you must begin with the true source -- it arose from the strike of a winged thing on Helicon, from Pegasus, child of Medusa.

Klimt, Pallas Athena

No comments:

Post a Comment